Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), high-grade B-cell lymphoma (HGBL) and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) start from mutated B cells that multiply uncontrollably. They are classified among the aggressive types of lymphoma.1,2

Although DLBCL, HGBL and PMBCL all start from mutated B cells (hence B-cell lymphomas), there are differences between these types of B-cell lymphoma.

Aggressive lymphoma can also develop from indolent (less aggressive) lymphoma. In this case, they are called transformed lymphomas. For example, an aggressive DLBCL can develop from an indolent follicular lymphoma.5 Follicular lymphoma usually grows slowly and occurs in many lymph-node sites in the body or in the bone marrow.3

In Singapore, lymphoma is the 4th most-common cancer in men and 5th most-common cancer in women. Over a five-year period from 2017 to 2021, more than 5,000 cases were reported in Singapore.6

DLBCL is the most-common type of lymphoma.3,7 The risk of developing the disease increases with age, with an average age of diagnosis in the mid-60s (but younger people can also develop DLBCL).3 Overall, men are slightly more likely to develop DLBCL than women.8

HGBL makes up just under a tenth of all DLBCL cases.9 PMBCL is also diagnosed less frequently than DLBCL: It accounts for around 2–4% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma and typically occurs in younger women in their 30s or 40s.10

It is still not fully understood what causes lymphoma. However, lymphoma happens when there are changes in the DNA of certain white blood cells called lymphocytes. These changes cause the cells to multiply quickly and uncontrollably.11

While the exact cause is unknown, some factors may increase the risk of developing lymphoma. These include:11,12

Read more about the development of lymphoma here.

Swollen lymph nodes in the neck, armpits or groin are usually one of the first symptoms people notice. Some people may also notice a lump or growth that doesn’t go away or gets larger.12

Depending on where the lymphoma has developed, other signs may include:13

Enlarged lymph nodes and spleen are often found in DLBCL.7 If DLBCL spreads to the bone marrow, normal blood formation can be inhibited. This can result in the following:14

Some DLBCL patients develop additional symptoms (B symptoms) such as fever, night sweats and unexplained weight loss.8

PMBCL develops in the mediastinum, which is the area in the middle of the chest behind the breastbone. As the tumour grows, it can press on nearby organs like the trachea (the airway leading to the lungs) or large blood vessels.3 This pressure can lead to symptoms such as:3

If a lymphoma such as DLBCL or PMBCL is suspected, your doctor will usually carry out a thorough physical exam. They will check for signs like swollen lymph nodes or an enlarged liver or spleen. As lymphoma can affect more than just the lymph nodes located directly under the skin, additional tests may be ordered.7 These tests may include:7

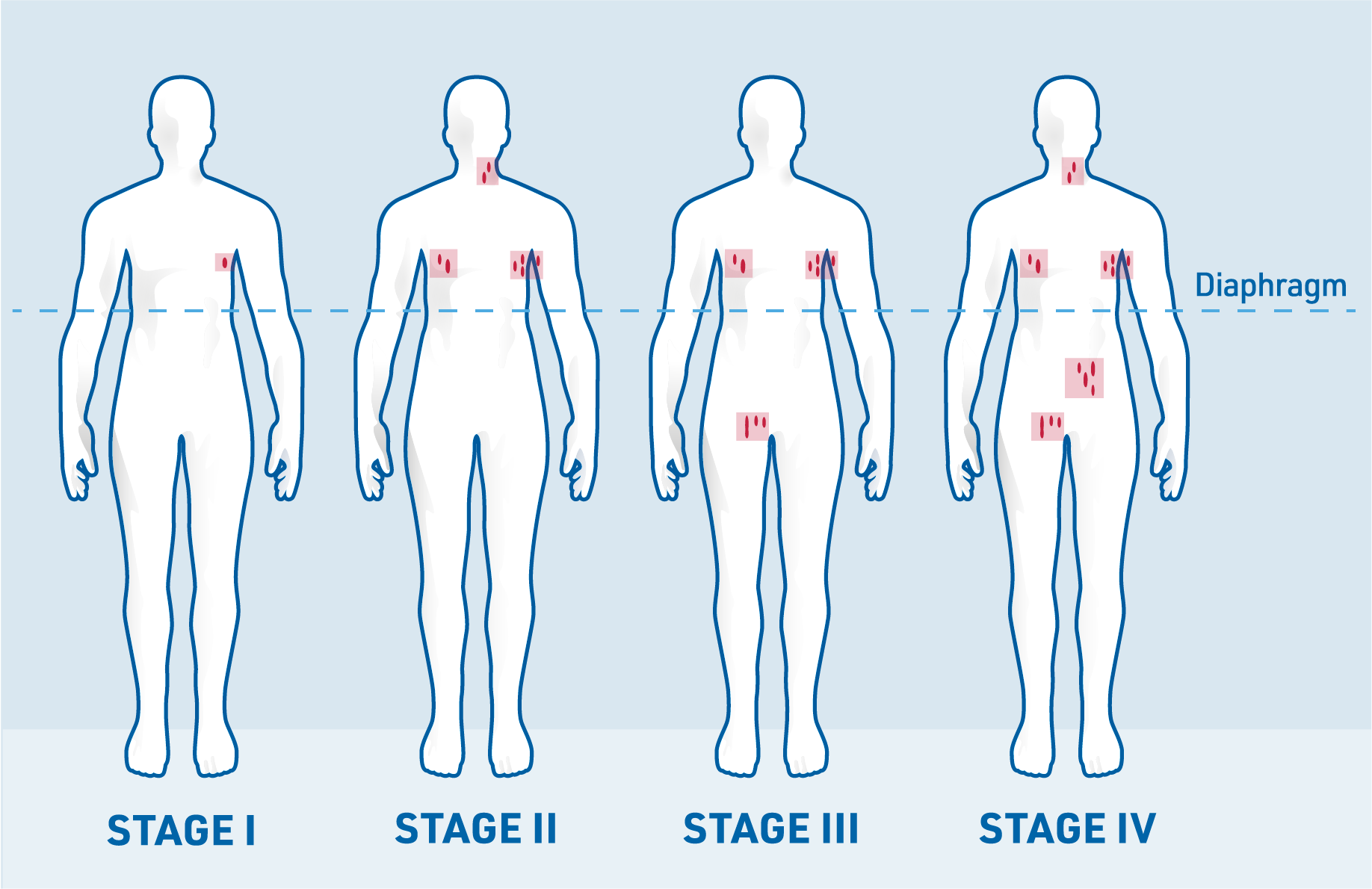

Staging the lymphoma is important to estimate the patient’s prognosis (outlook) and guide treatment decisions.7

Doctors use diagnostic tests, such as physical exams, imaging and biopsies, to determine which parts of the body are affected by DLBCL. Based on these results, the disease is staged according to the Ann Arbor classification system, which helps describe how far the lymphoma has spread in the body.7,15

The stages of the Ann Arbor classification can be summarised as follows:7,15

Stage I: Involvement of a single lymph node region

Stage II: Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm

Stage III: Involvement of lymph nodes or structures on both sides of the diaphragm

Stage IV: Diffuse organ involvement, for example of bone marrow and/or liver

Apart from the Ann Arbor classification, other factors can influence how a patient responds to treatment. These factors help give a clearer picture of the patient’s prognosis (the likely course of the disease).15

The International Prognostic Index (IPI) is a tool used to estimate a patient’s chances of recovery or how well they are likely to respond to standard therapy. The following risk factors are considered:15

Depending on the number of risk factors the patient has, their risk level is classified as low, low–intermediate, high–intermediate or high.15

People diagnosed with lymphoma, including DLBCL, should receive care from specialists in haematology and oncology. These experts work in specialised departments within hospitals, clinics or dedicated practices.7,16

Treatment plans depend on the stage of lymphoma. If treatment is started at an early stage, approximately 65% of people are still alive after 5 years after diagnosis.12 As DLBCL is an aggressive and fast-growing type of lymphoma, treatment should be started as soon as possible after diagnosis.12,13

The standard treatment for DLBCL is chemoimmunotherapy. Older or less-fit people may be given a less-intensive treatment combination, for example, excluding certain drugs from the treatment regimen or lower doses of drugs.13

Treatment of PMBCL is usually based on that of DLBCL in first-line therapy.17

Treatment for HGBL varies depending on the particular genetic rearrangements (parts of genes switch places within chromosomes) that are present. When you are diagnosed, your doctor will perform some tests to see what type of HGBL you have. Based on this, your doctor may recommend different types of chemoimmunotherapy, radiation or a clinical trial.18

The treatment of relapsed (returning) or refractory (resistant to initial treatment) DLBCL, PMBCL or HGBL depends on factors such as the patient’s age, overall health and the timing of the relapse.8,18

For patients with a late relapse (longer than 12 months after initial therapy), treatment typically involves:8,18

For patients who relapse earlier (less than 12 months after initial therapy), CAR T-cell therapy or participation in a clinical trial are often advised.18

Both CAR T-cell therapy and autologous stem cell transplants aim to cure the disease, however, this is not the case for all patients.18

For patients who are not candidates for stem cell transplants, treatment options include:8,18

If you have relapsed or refractory PMBCL, your doctor may also offer you immunotherapy as a treatment instead of CAR T-cell therapy or a stem cell transplant18

After treatment has ended, doctors carry out a final examination to check how well the patient has responded to the therapy.17 If the tumour can no longer be detected with imaging, the patient may be considered to be in complete remission. At this point, a follow-up program begins.17

Follow-up care after lymphoma treatment is crucial for several reasons. It aims to:17

During follow-up visits, healthcare providers will focus on:17

Reviewing your medical history and performing a physical examination

Performing laboratory tests to check for any abnormalities

Recommending further imaging procedures, such as ultrasounds or X-rays, if necessary, based on your specific condition

Maintaining a regular follow-up schedule is essential to monitor your health. A typical follow-up schedule is:17

Please make sure you speak to your doctor regarding the follow-up schedule as the monitoring frequency may vary.

References: