Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that begins in B cells, a type of lymphocyte that plays an important role in fighting infections. In MCL, these B cells multiply uncontrollably within the lymph nodes. Over time, the cancerous B cells can spread to other parts of the body via the lymphatic system.1,2

MCL gets its name from the mantle zone of the lymph nodes where the abnormal B cells usually develop. MCL occurs when these B cells mutate and begin to grow out of control, forming cancerous cells.3,4

MCL accounts for approximately 5–7% of all lymphomas and is therefore a rare form of cancer.3 Men are more likely to develop the condition than women.4 MCL is usually diagnosed in people who are middle aged or older; It is very rare in young people.4

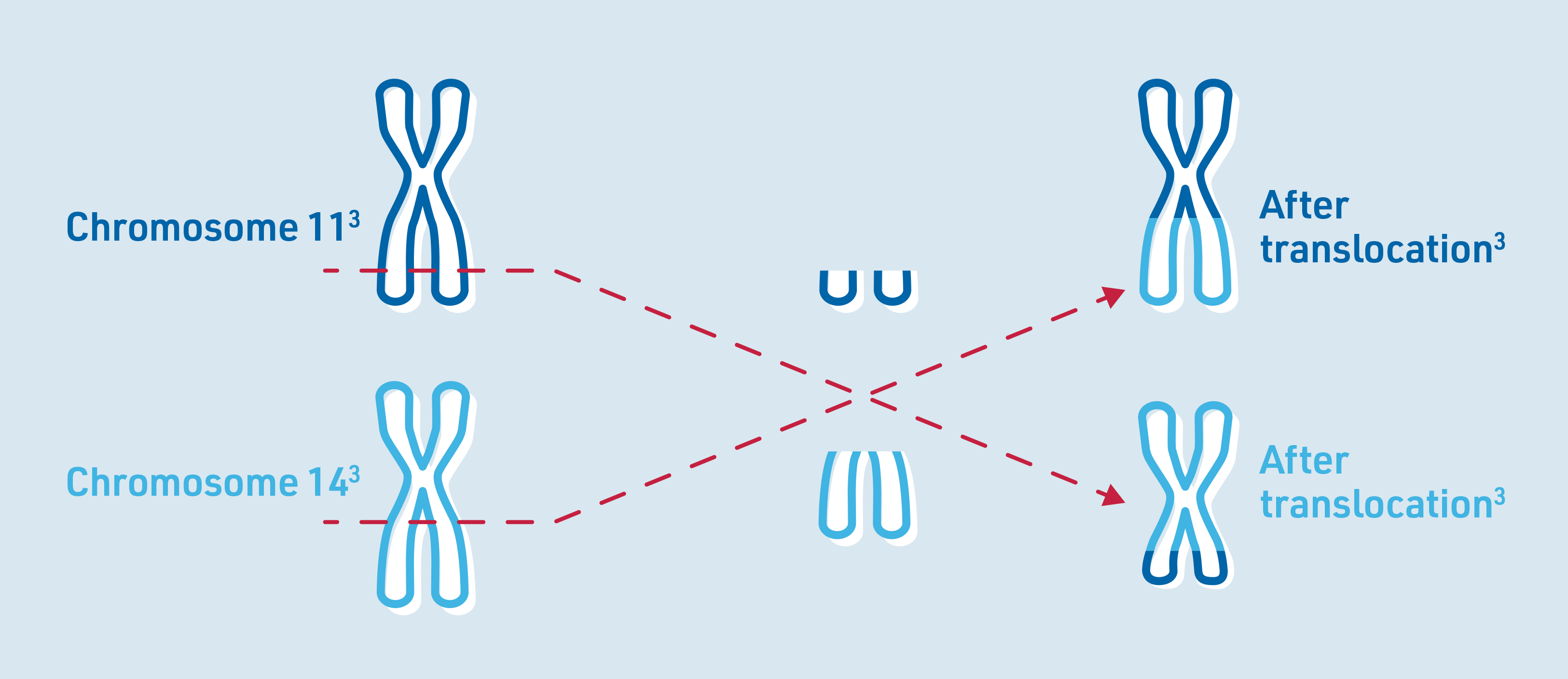

While the exact cause of MCL isn’t fully understood, most cases involve a specific genetic mutation called a chromosomal translocation.3,4

In MCL, a piece of chromosome 11 and chromosome 14 breaks off and switches places with the other chromosome – this is called a translocation. This genetic change leads to the overproduction of a protein called cyclin D1, which contributes to the uncontrolled growth of B cells. This uncontrolled growth is a key factor in the development of MCL.3

Chromosomes are structures in human cells that store genetic information. Made up of DNA, chromosomes contain genes, which are responsible for passing on inherited characteristics. Healthy human cells typically have 46 chromosomes – 23 pairs with each chromosome appearing twice. These chromosomes are numbered from 1 to 23.3,5

If MCL is suspected, doctors can perform tests to see if a translocation has occurred between chromosomes 11 and 14, or if there are increased levels of protein cyclin D1. Identification of this translocation is crucial to distinguish MCL from other types of lymphoma. In addition to this translocation, other genetic mutations may also play a role in the development of MCL.3

There are a range of factors that may contribute to the development of MCL including:3

MCL is associated with a range of symptoms that can often be mistaken for common physical ailments.1 The most-common symptom of MCL is painless swollen lymph nodes which may develop in several parts of the body.3,4

Additionally, if the cancerous cells spread to the bone marrow, it can disrupt blood formation leading to:4

MCL may also spread outside of the lymphatic system and the resulting symptoms depend on which area of the body is affected.4

Some people may also develop some general symptoms, known as B symptoms:3

Diagnosis and staging

If MCL is suspected, the doctor will:1

These tests help not only confirm the presence of MCL, but also determine how far the disease has spread in the body.1,3

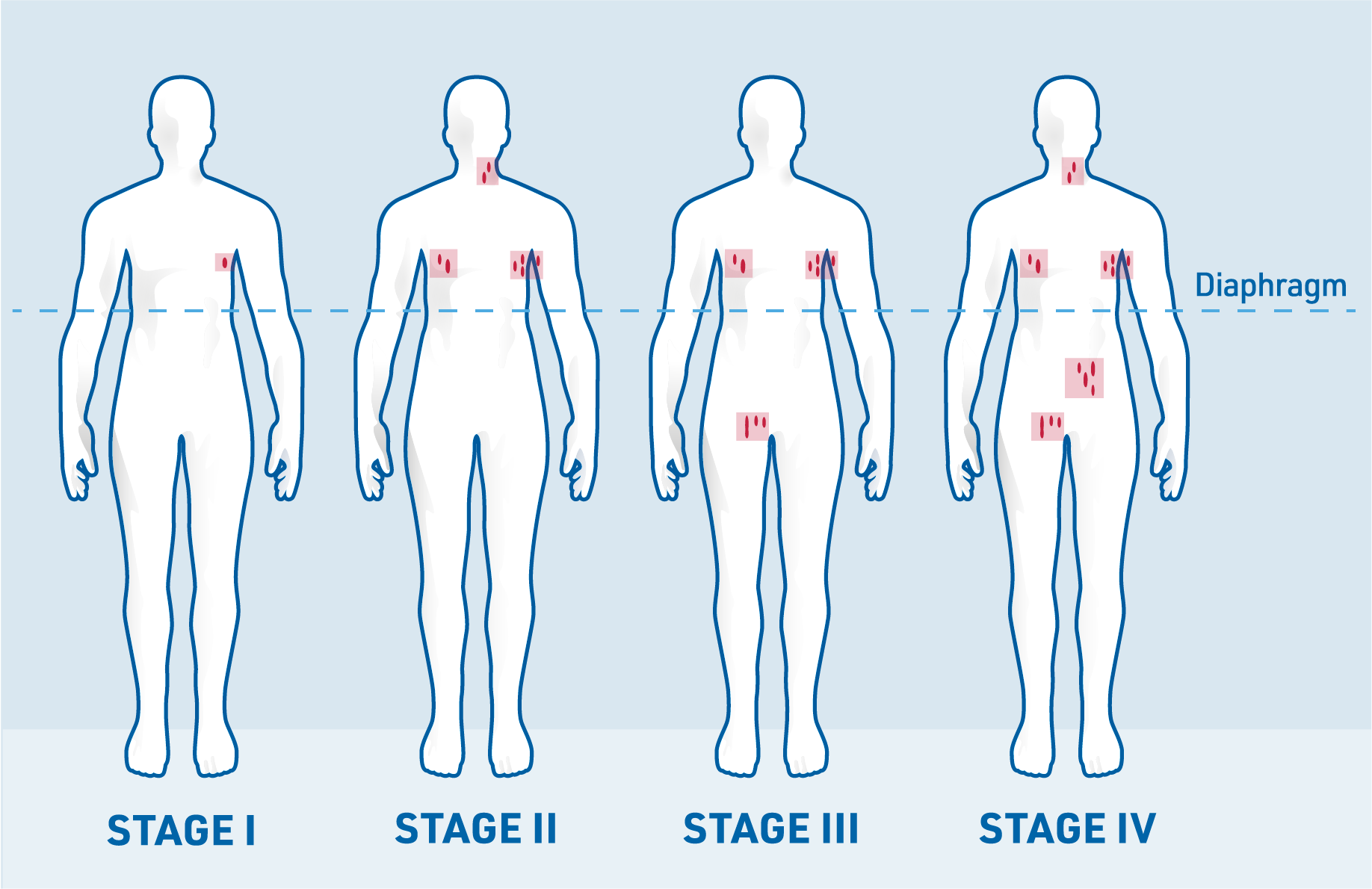

The Ann Arbor classification divides MCL into different stages that describe where cancer cells are found in the body:3

Stage I: Involvement of a single lymph node region

Stage II: Involvement of several lymph node regions on one side of the diaphragm

Stage III: Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm

Stage IV: Diffuse organ involvement, for example of bone marrow and/or liver

In addition to the stage of the disease, certain risk factors can help estimate the patient’s prognosis and guide treatment decisions. One important measure is the tumour’s growth rate, determined by the marker Ki-67, which indicates how fast the lymphoma is growing6

Doctors also calculate the Mantle Cell Lymphoma Prognostic Index (MCPI), which helps estimate the likelihood of MCL relapsing (disease return) after treatment.4

The following risk factors are considered when determining the MCPI:4

Treatment for MCL should always be managed by experienced haematology and oncology specialists.3 Optimal therapy depends on several factors, including:3

Watch-and-wait strategy: If MCL is diagnosed in its early stages and is slow growing, a watch-and-wait approach may be recommended. This strategy involves closely monitoring the disease without starting treatment immediately, with treatment beginning only if the lymphoma spreads or symptoms worsen.3,4

Common treatment options: The most-common treatment for MCL is chemoimmunotherapy, a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, which is designed to target cancer cells.1,3 In some cases, other treatments may be considered, including:1,3,4

Goal of treatment

The goal of MCL treatment is to achieve remission—meaning no signs or symptoms of cancer.3

Treatment for MCL depends on the extent of the disease at the time of diagnosis.

Patients in stages I and II may first be treated with chemoimmunotherapy in combination with radiotherapy to the affected site3

For most patients, MCL is only detected at an advanced stage and progresses rapidly.3 Depending on the patient’s age and general physical condition, the doctor can use different drugs or combinations of drugs. Younger and fitter patients may be given chemoimmunotherapy, particularly high-dose chemotherapy, followed by autologous stem cell transplant (autologous means the transfer of the body’s own cells or tissue)3

After a relapse, patients may be treated again with chemoimmunotherapy. The specific drugs used will depend on the medications the patient received during their first round of treatment. This approach combines chemotherapy with immunotherapy to target cancer cells.3,4

For physically fit patients who have already undergone an autologous stem cell transplant (using their own stem cells), an allogeneic stem cell transplant (using stem cells from a donor) may be an option. In this procedure, healthy stem cells from a suitable donor are used to replace the patient’s damaged cells.4

Targeted therapies are one of the most-common treatment options for relapsed or refractory MCL. These therapies focus on specific proteins or pathways that help cancer cells grow and survive, effectively disrupting their function.3,4

CAR T-cell therapy is an innovative treatment in which the patient’s own T cells are genetically modified to recognise and attack cancer cells. These modified cells have a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) on their surface, enabling them to identify and kill cancer cells as threats to the body.4,7

References: